Splitting Equity Today

Dividing equity between each co-founder tends to be one of the biggest mistakes we make. In this section of our Equity Series, we'll explain how to divide Founder equity in a way where we split equity fairly, not just based on future contributions but actual contributions.

August 23rd, 2022 | By: The Startups Team | Tags: Funding

Welcome to Phase Three of a four-part Splitting Equity Series. If you missed it, start your journey here: Introduction - Early Startup Equity — Getting it Right before continuing on if you haven’t already, and go in order from there.

Phase One - Startup Equity - Avoiding Early Mistakes

Phase Two - How Startup Equity Works

Phase Three - Part 1 - How to Split Equity

Part 2 - Splitting Equity Today ( ←YOU ARE HERE 😀)

Part 3 - Splitting Equity in the Future

Phase Four - Equity Management

Let's continue!

Startup founders have been trying to figure out a fair equity split for the founding team since the dawn of time. Sadly, dividing equity between each co-founder tends to be one of the biggest mistakes we make.

Let's explain how to divide founder equity in a way where we split equity fairly, not just based on future contributions but actual contributions.

Realistic Founder Equity Splits

The biggest question startup founders wrestle with is how to divide equity ownership at inception. There are about a dozen different types of expected contributions, but they generally fall into two buckets — cash and non-cash contributions.

Cash Contributions. Actual cash invested into the company that is spent.

Non-Cash Contributions. Time (sweat equity), relationships, the idea, tangible resources.

The process of converting our contributions to startup equity is as easy as tallying up the sum total of everyone’s contributions (present and future) and weighing them appropriately. For the moment we'll talk about splitting a startup's equity among co-founders in Year 1, and then talk about equity distribution for ongoing contributions later.

Real World Equity Splits for Co-Founders

All of our present and future contributions are going to be based on real-world, Fair Market Values – which means we don’t get to just “make up” an equity grant based on a number that just “sounds good”. A surprising number of co-founders start with equal equity splits until eventually, one co-founder decides that didn't work out so well (it happens a lot!)

Instead, we're going to be splitting equity among co-founders (and later early employees) based on real-world contribution values whenever we allocate equity. Instead, we are going to use real-world values for every contribution.

Splitting Equity based on Contribution

An intern or random family members don’t get 20% of the company just because they happened to be present at the very beginning. Our key hires and co-founders need to be able to convert their future contributions into a real-world value that can be properly accounted for as the company grows.

In addition to showing an actual value within our equity split, it also creates real accountability. If Feargus the intern gets an equal equity split of 20% of the startup equity, regardless of whether it's earned or contributed, it's a bad deal! Real-world values are far easier to track because they look and feel like money – which they essentially are.

The Equity Split "Value Multiplier"

Before we begin valuing our contributions to split equity, let’s first understand how our contributions are calibrated for the type of risk a startup inherently has. Potential investors understand the opportunity cost of investing, but when we split equity among founders in the early stages, not everyone values the risk quite as much.

Comparing Cash vs. Sweat Equity

Not every co-founder's contribution is created equal — some contributions are simply worth more than others based on scarcity.

For example, $1 of cash invested is more valuable than $1 of sweat equity (time) invested for a multitude of reasons. It’s more scarce, it’s more versatile (can be used to purchase many things), and it’s harder to replace. If we’re not sure, let’s try starting our company with purely “sweat equity” to pay our first key hires and see how far that goes!

Applying a "Value Multiplier" to Contributions

All contributions have a risk associated with them, given the nature of our business. The risk of co-founders investing $1 into a startup is much higher than say a publicly traded stock.

Therefore, we apply something called a “Value Multiplier” so that cash and non-cash contributions can get weighted a bit differently. We don’t need to get too complicated here. We simply apply a value multiplier of cash versus non-cash:

Cash is worth 4x more.

Non-cash is worth 2x more.

Don’t agree? No problem! We can adjust the modifiers to be anything we want – or use none at all. The intent here is to value the risk someone is taking by investing those assets into our business at such an early stage. This will become even more important as we look beyond our founding team to create a fair equity split for key employees, board members, or a potential angel investor.

Cash Contributions from Co-Founders

Cash contributions are the easiest to value. We take the value of the cash invested, multiplied by the “value multiplier” and tally up the actual value to split the equity.

Example of a Cash Multiple:

Cash Invested ($1) x Value Multiplier (4x for cash) = $4 Contribution

There are a few caveats here. In order for cash to be officially “contributed,” it needs to have been transferred to the business. If I say “I’m committing $1 million to the company” but only transfer $100 into the account, I haven’t really invested $1 million.

I need a mechanism to “commit” the capital, which can be as direct as transferring into the company’s checking account (which is what an investor would do) or at least having a legal agreement that either requires I put the remaining balance in or have my contribution value forfeited.

Loans as Cash

Sometimes the investment may come in the form of getting a bank loan or other securitized investment. In almost every case, this will require someone to secure the loan by virtue of signing for it personally.

In that case, the question becomes, “Should the value of the loan be treated as ‘cash’ and if so, should the person who secured it get the benefit of the cash value even if the business is paying it back?”

It’s a good question and in this case, there are a few answers depending on how all parties involved (particularly the co-founder signing) feel about risk.

3 Options for Applying a Loan Multiplier

Option 1: Signing parties get cash value. In this option, whoever signs gets awarded the cash value (with cash multiplier) of the loan, regardless of whether it’s paid back. Use this if we agree that the risk of the signature at the time of signing is where the reward is made. Like any investment, if it pays off, then theoretically there is no risk, but we have to assume 100% of that risk to find out.

Option 2: Signing parties get half value. In this case, we’re feeling like the risk to the loan is relatively small (maybe it’s not a big loan or there is some other way to guarantee that it will likely be paid off) and therefore the signing party gets a 2x multiplier (half of the 4x cash multiplier).

Option 3: Signing parties get a small discount at payoff. In this option, the signing parties get 4x as a cash multiplier and then get a small discount (for example, 20% less) once the loan is paid off. This accounts for a balance between the risk of signing and the benefit of the business paying off the loan.

Each option allows us to calibrate how all parties assess the riskiness of the loan as well as the probability of it being paid off. Since the signing party is on the hook for the loan, whether or not it came out of their bank account is irrelevant – they still have a balance to account for.

Non-Cash Contributions

Anything that isn’t cash falls into the non-cash contribution. Most of this involves time invested, but can also include things like relationships, office space, intellectual property, or the original idea itself. Each of these mechanisms tends to have a fair market value that we can approximate which makes our approach fairly standard.

Suggestion:

Non-Cash contributions are valued at 2x their fair market value.

Founders will need to discuss expectations for what equity share they could earn from non-cash contributions, but as a serial entrepreneur will tell you, these expectations often morph as startups mature.

Time (Sweat Equity)

The most common investment amongst startups is time. In order to value the time we take the average market rate we would be paid (relative to this industry, geography, and stage of the business) divided by 2,000 hours in the year and then multiplied by the number of hours we will commit.

Example 1: Ongoing Founder investment

If I’m a software developer from Columbus, Ohio that would normally earn $100,000 per year, and I plan on working 50% of the time on the new startup, I would be making a $50,000 contribution in Year 1. We would multiply that contribution by 2x for a total of a $100,000 Year 1 Contribution.

Example 2: Contractor on a Single Project

If I’m a contractor working on a specific project, we would take the contract value ($10,000) and apply a 2x multiplier against it for a $20,000 single contribution.

Remember that our value contribution of time needs to be correlated to what our startup can reasonably pay. If a Harvard Business School CEO otherwise makes $1 million per year working at a publicly-traded company that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a $1 million contribution to a startup!

That's because a startup may not be able to use that same skill set nor would they be in the stage of their business to offer that salary — it might be the wrong partner. There’s no perfect formula here, we have to use some reasonable judgment.

Relationships

Sometimes providing a connection to potential investors, customers, co-founders, or talent can have a real contribution value and help a future valuation. The trick here is that we apply a “market rate” for that contribution once it has been made, not when it’s still being considered (same as all other contributions). As such, the contribution would need to be “paid for” once it’s consummated.

If the relationship was for hiring a salesperson, and the market rate for a recruiter is 25% of salary (which let’s say was $100,000) then we’d owe the contributor $25,000 multiplied 2x = $50,000.

If the contribution was a connection to a major customer we would offer a commission for the introduction, and perhaps more if they facilitate the full sale. That commission rate should be discussed so that an actual dollar value can be assigned, depending on our business strategy.

The two factors here are “what’s a market rate for this type of transition” and “what trigger confirms it has been provided?” Only then do we want to divide equity.

Facilities and Hard Goods

Some items will have a very “real” fair market value such as office space, equipment, inventory, and hard goods. A car-sharing company like Uber might have one Founder that can provide some vehicles for example. Offering these products can have what appears to be “cash value” however in most cases they don’t have the same versatility as cash and therefore don’t command the same value premium.

If someone is contributing office space that would command $2,000 per month in the open market, they would be contributing $2,000 x 12 months = $24,000 which would then apply a 2x Value Multiplier = $48,000 in Year 1.

In each case, we’ll assess the quantity of the contribution multiplied by the fair market value within the first year. We can then add additional contributions in Year 2 and beyond.

Ideas and Intangibles

There’s a whole category of intangibles that we will often also consider based on our particular situation. The most common one is “the idea” or business plan, although this could be extended to anything that falls outside the scope of easy-to-value assets.

Note that ideas and intangibles may not require a Value Multiplier to be used since they often don’t have any “risk” associated with their contribution. The Value Multiplier is mainly targeted toward contributions that otherwise have a market value that would be rewarded without this risk.

In this case, the best way to value the “idea” is to think of it as a licensing deal. “What would it be worth for us to license or buy this idea?” We can’t say “I have an idea that could become Facebook. Facebook is worth $100 billion, so my idea is worth at least $100 million.” No, it isn’t. The execution, capital invested, and time invested over the next decade are what make the idea worth something. Right now the value of the idea or other one-off should be considered a one-time cost based on its net present value.

“I have an idea for the next Facebook. I’m willing to license it to you for $50,000.”

We can’t sell something beyond what a startup can pay for it now, and if “buying the idea for $1 million” seems like a fair price — so be it. But we should be mindful that everything has a price and it should be translated to real-world dollars today, not “what it could be worth someday.”

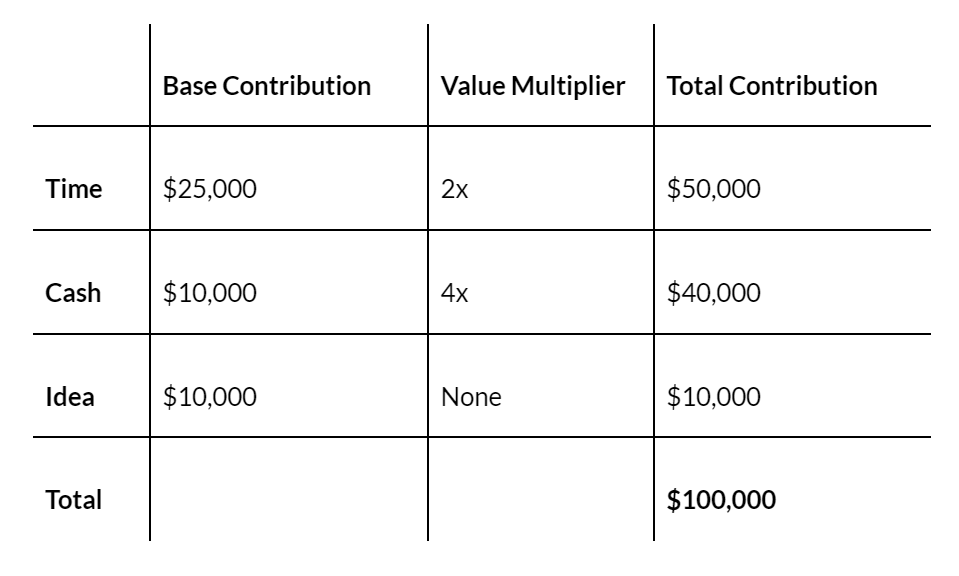

Calculating Year 1 Contributions

Now that we understand how to value each contribution, all we have to do is sum them up to get a total Year 1 contribution for each member. The calculation uses the intended Year 1 contribution, multiplied by the “Value Multiplier,” to show a total contribution to the company.

Here’s an example of my contribution to the company in Year 1:

In this instance, I’ve contributed cash, non-cash, and “one-off” contributions (the idea) which each have their own multiplier. This creates a $100,000 contribution to the company.

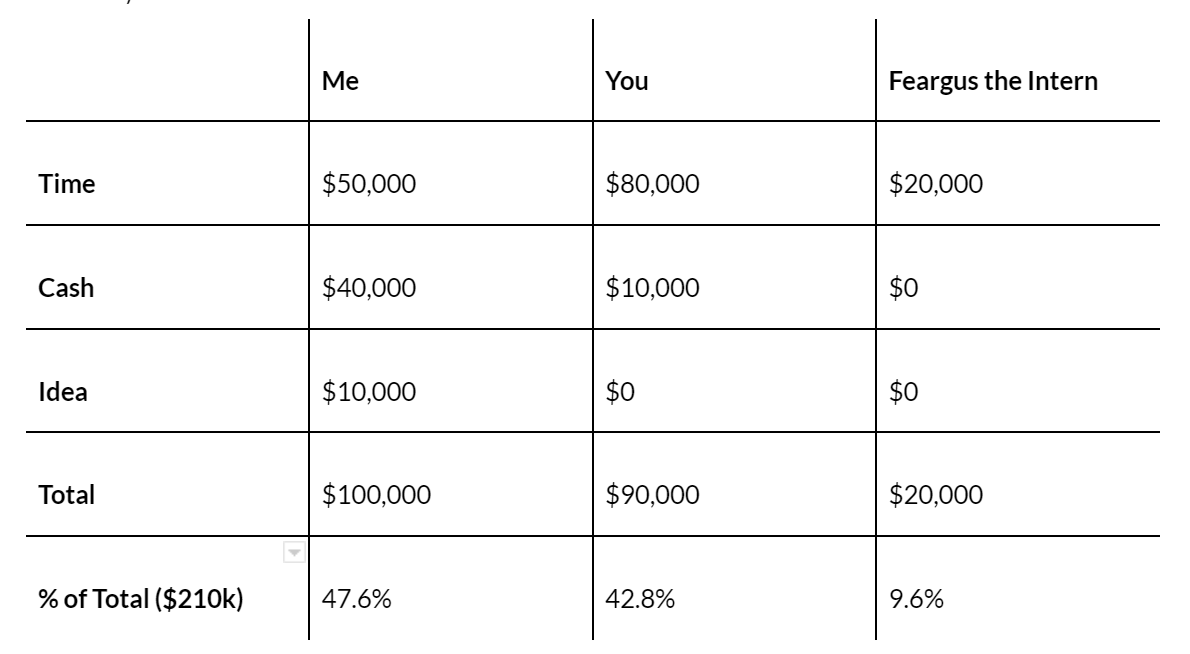

When we calculate everyone else’s contribution in Year 1 we will use the same formula. This will help us determine how equity splits will work relative to the contribution amount each person will make in Year 1.

Here’s an example of how our respective contributions might break out in Year 1 (with multipliers already factored):

As this example indicates, your time is coming in at a higher value, either because you have a higher market rate, or you worked more hours. Feargus isn’t contributing cash so he’s simply paid based on his relatively low market rate, but still gets a multiplier based on the risk of non-cash contributions at 2x.

How to Manage and Audit Yearly Contributions

In order for this process to work, each year we will need to propose our intended contributions and then audit those contributions at the end of the year. This way we can compare what we intended to contribute with what we actually contributed.

We do this in two steps. We start by proposing our contribution at the start of the year, and then at the end of the year reviewing last year’s contributions while making new ones for this year.

This is where this method is most useful!

During the formative years in a startup, it’s damn near impossible to project how many resources any one person would put into the startup. So many things change so quickly, especially when we’re defining the job and the company as we show up each day. This is also why making a one-time equity split based on Day 1 is almost certainly going to fail - we have no option to refine our contribution.

Yearly proposals and audits keep everyone honest and essentially force a conversation about commitment for the coming year. It’s a healthy dialogue all around. Also, if everyone knows they have to actually stand by their commitments (because they are audited) it provides for a much more consistent contribution.

Step 1: Lock Down Proposals

At the start of each year, and certainly, when we initially set up the cap table, we’re each going to propose our contributions. If other participants join later in the year — no problem. Just pro-rate the contributions for Year 1 and then we can get them on the same cycle as the rest of us.

The proposals give us an indication as to how much stock we will earn, but also give us a basis for comparison at the end of the year. For example:

If I commit $10,000 to the company (which would give me $40,000 with a 4x multiplier) but only ever invest $1,000 into the company, we would make the necessary adjustments at the end of Year 1.

An important part of this exercise is each of us considering our intended commitments and locking them down publicly. It’s really easy for folks to “forget” what they said they would commit early on and then later adjust their memory to their current contribution. The proposal each of us makes now should be time stamped and circulated to all participants, so we have a public record of what was said. We don’t need a scribe preparing a scroll at the town hall forum — a group email works just fine!

Step 2: Audit Last Year

On the anniversary of our first full year, we’ll sit down and compare our contributions to our proposals. Sometimes this may take all of 5 minutes – we’ll both say “Yep, we both stuck it out 100% and it’s all good.” And we’re done.

After Year 1, though, it’s not uncommon for that to be a very different conversation. In many cases, we may find that our intentions from the outset of Year 1 specifically are very different than where we landed. There’s a good chance that the one developer who was so excited about helping us build the mobile app got completely derailed in Month 2 and put in 20% of the effort they had committed to. Now is the time to audit that contribution and have a discussion about next year.

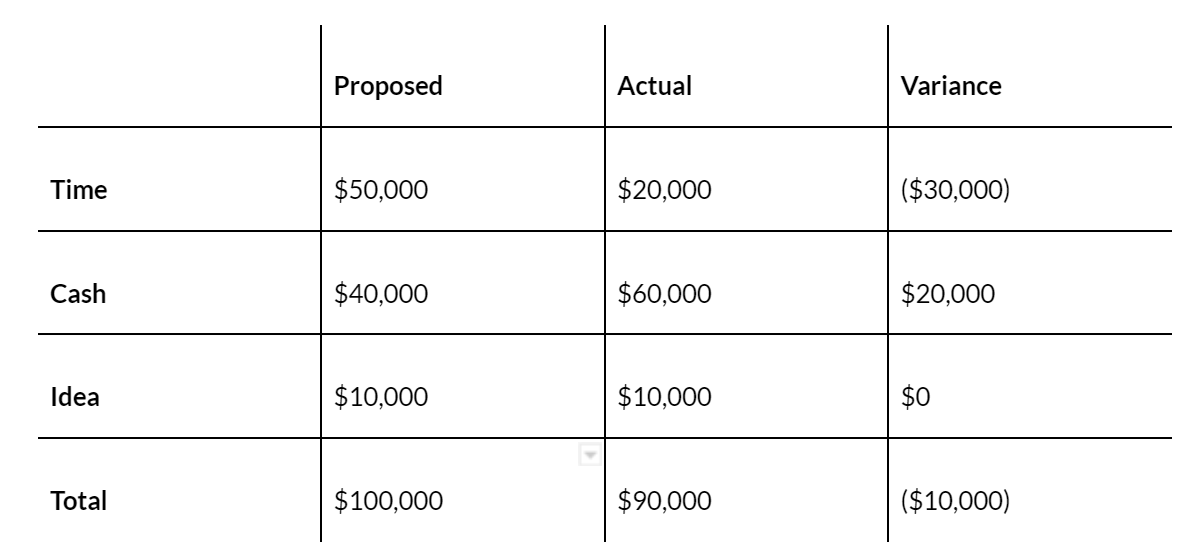

Within the audit, we’re going to calculate each proposed contribution versus the actual contribution and true up the numbers.

Heads up!

This is especially important if certain members have made contributions beyond what was proposed, such as contributing more cash or working substantially more hours. Unless there is a mechanism to deliberately recognize and reward members — these contributions will feel “lost” — and that’s a problem.

After our Year 1 Audit, we may revisit our contribution table and have it look like this:

Year 1 Contributions – Post Audit

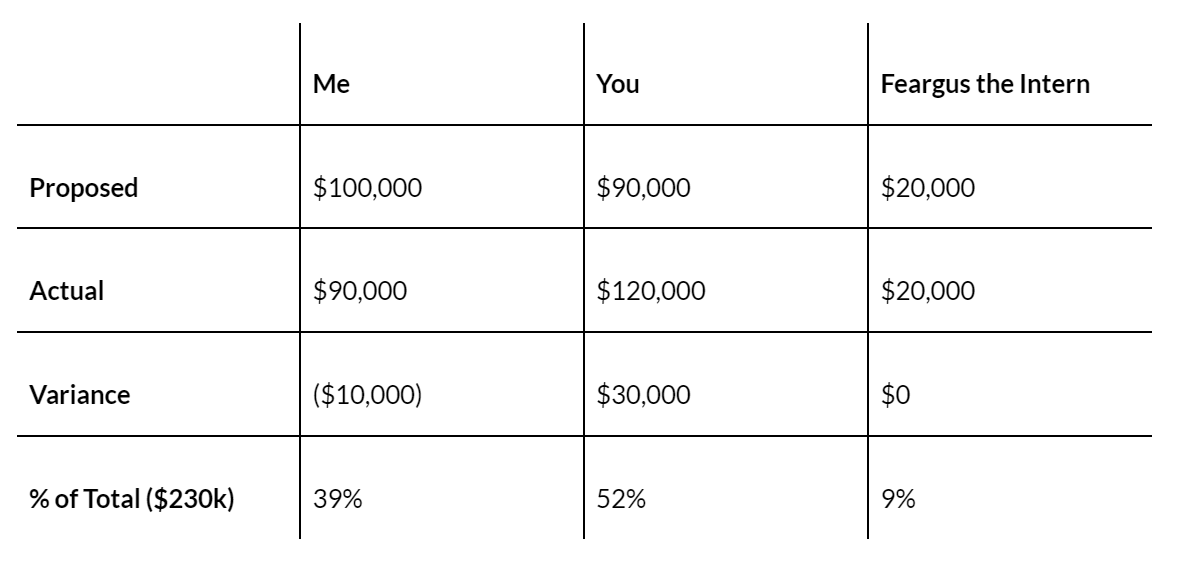

Now the math starts to get a bit different because each person’s contribution will be relative to everyone else’s contribution.

When we initially proposed our contributions, the total of all of our contributions was $210,000. Yet, at the end of the year, each of our contributions will likely have shifted a bit. If I were to contribute 10% less than I proposed, but everyone else also contributed 10% less, our relative positions would stay the same. This keeps things very fair relative to each actual contribution.

After the Year 1 Audit our team contributions may look something like this:

Here, Feargus stuck with his original commitment and came out about the same. But your commitment wound up being much larger than anticipated, even though mine wasn’t far off, and relative to Year 1 you earned more of the stock. That’s fair. The more you contribute the more value the company should be getting, and the more you should be rewarded.

We’ll keep a record of the audit that we will also share amongst all the members (date stamps matter) whereby each member needs to confirm that they have seen the record and agree with it. If someone doesn’t agree, the conversation needs to open up about why.

The First Time is Often the Hardest

The first-year audit may be more challenging than the following year only because it’s the first time people have to come to terms with both their contributions, but also how their relative stock rewards are affected. It’s a good exercise though because it directly relates to how folks view their participation.

Step 3: Next Year Proposals

After our year-end audit, we will then submit a fresh round of proposals each year, recognizing that what we intend to propose and what we can deliver upon will probably get more accurate year over year. In some cases we will just literally copy/paste our proposal from the previous year and be done with it – that’s fine.

What matters is that we have a moment to think about it and discuss it. There’s something immensely satisfying about seeing each member on the team “re-up” for another year and knowing that everyone is as committed as we are.

Things Change in a young company And That's Okay.

Conversely, there’s something incredibly useful in knowing that we have a chance to deliberately dial back our commitments if we can see that life is getting in the way of sustaining them. That’s OK! There’s nothing wrong with saying “Hey, I’m going to have to dial back my commitment 50% this year so that I can continue to work at my day job as well.” The yearly proposal should be a time of reflection and support.

Rinse. Repeat. Split Equity.

This process is fairly straightforward and should continue each year until we have reached our total “Contribution Window” (typically 3 years) which leads us to our next question of how to set a contribution window length.

Oh look, whaddya know — that’s up next!

About the Author

The Startups Team

Startups is the world's largest startup platform, helping over 1 million startup companies find customers, funding, mentors, and world-class education.

Related Articles

Unlock Startups Unlimited

Access 20,000+ Startup Experts, 650+ masterclass videos, 1,000+ in-depth guides, and all the software tools you need to launch and grow quickly.

Already a member? Sign in